Teaching in the open means that you are making some or all aspects of your learning environment available and accessible to the public. For some, this may mean the adoption of an open text or learning resource, or contributing open educational resources created by you and/or your students. For others, it may mean adopting a set of open practices – related to all aspects of the course including planning, learning, assessment and reflection on the process. As evidenced in the great work that faculty and students are engaged in at UBC, there is no one right way to “do open.”

Open teaching may include:

- Use of an open textbook and open resources in a course (see the Guide to Finding OER and the Guide to Finding Open Textbooks for more information)

- Using student blogs as open portfolios where they can document, share experiences and get feedback on their work (or works in progress) from a wider audience than their course mates or instructors. Example: UBC Blogsquad.

- Opening a class discussion to the public via open course blog or via Twitter hashtag. Example: ArtsOne Open

- Students creating openly licensed learning resources and publishing them (via YouTube, Flickr, Google docs or other platforms). Example: Digital Tattoo Project

- A fully open course using open resources and engaging students from all over the world. Example: (UBCx)

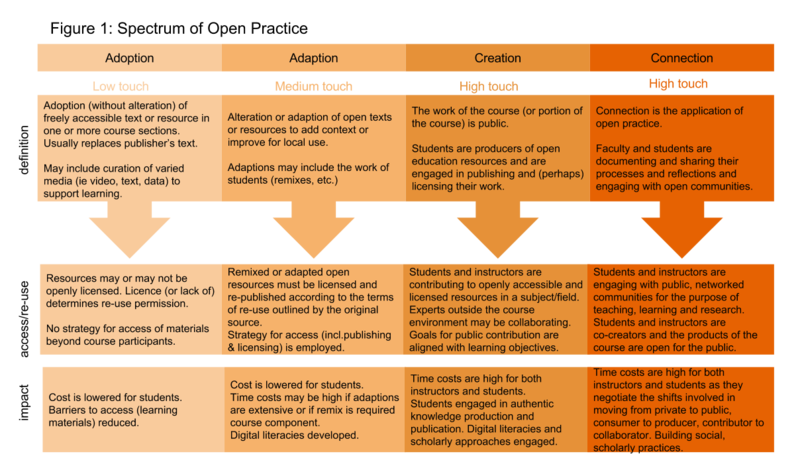

In general, openness isn’t a single expression and exists on a spectrum as shown below.

- Low touch vs. high touch: the concept of “touch” that we have articulated here refers to notions of interaction between and among participants in the course as well as interactions with “public” communities and individuals. This may also have an impact on the design effort related to the course. For example courses supporting interaction with various external communities and resources over a period of time (wikipedia editing; publishing on YouTube; etc) require a high touch approach to the design and also to the ongoing support of those interactions.

Adoption

Adoption of an open copyright licensed (e.g. Creative Commons) resource is a good first step to engaging in open practice. Replacing a high cost textbook with an open textbook or other open resources (e.g. videos, simulations, etc.) reduces barriers for students to access course material needed for their success. According to the UBC AMS 2019 Academic Experience Survey results, 71 per cent of UBCV undergraduate students who responded reported that they have gone without textbooks or resources due to cost at least once, with 35 per cent of students reporting they frequently or often go without textbooks due to costs. Adoption of an open resource supports all students achieve success by providing equal access to all resources available in the course regardless of their finances.

Examples

The following are examples of open resource adoption by faculty at UBC:

- Introduction to Physics (PHYS 100) adopted an Open Stax Textbook at UBC in 2015 saving $90,000 in textbook costs

- Math, CS lead in adopting open education resources at UBC

Adaption

Adaption is the modification or alteration of an open copyright licensed resource for use within a course. Adaption provides the opportunity to improve teaching materials, provide important local context, and sharing knowledge to ensure sustainability and the ongoing health of open content. There are a variety of ways content can be adapted for course use – instructors adapt content and/or students adapt content for their own use. Including students in the adaption process encourages peer-to-peer learning, authentic learning opportunities, and digital and information literacy development.

Examples

The following are examples of open resource adaption by faculty at UBC:

- Jonathan Ichikawa (Philosophy) adapted an open logic textbook called forall x, by PD Magnus, and created forallx: UBC editionfor use in PHIL 220.

Creation

Creating open resources

Many teaching materials can be openly licensed and made available for others to revise or reuse, such as syllabi, lecture notes, presentation slides, case studies, videos, podcasts, study questions, quizzes and more. Some faculty choose to create entire open textbooks. Of course, there may be some you don’t want to share because you want to reuse them in future years yourself (e.g. exams). But you may be willing to share other materials. Even if you think other teachers or students might not find them valuable, even if you think they are very specifically tied to your course context, you might be surprised at how they could spark ideas in others to use in their own teaching.

To make your teaching materials open, you need to give them an open license.

For more on creating open educational resources, see the Guide to Creating OER.

Examples

The following are examples of open resources created by faculty at UBC:

- Jon Festinger (Allard School of Law) has created a WordPress site for his Video Game Law course, on which he posts the syllabus, videos, notes, and more, with a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Open assignments

One way to think about open assignments is asking students to share their work with others beyond the instructor or Teaching Assistant. This can be public sharing with or without an open license. Students should always be given a choice whether or not to share their work openly, and they must choose whether they want to give it an open license, and if so, which one (since they are the original creators of the work).

- For example, one could ask students to do course assignments on open platforms such as blogs (e.g. UBC Blogs) or wikis (e.g., UBC Wiki); these are publicly available, and students could choose to add an open license or not.

- Students could create videos, slide decks, images and more and post them to public sharing sites (with an account that doesn’t identify them if they wish, or the instructor could post to a sharing site for the students).

- One could provide an option for students to post their work with a pseudonym if they choose, or to send it just to the instructor/TA if they don’t want it to be publicly available.

Examples

The following are examples of open assignments at UBC:

- Students in Geography at UBC have created multiple kinds of educational resources that are posted on a public site, including case studies, infographics, videos and more: http://environment.geog.ubc.ca

- Students in MECH 436/536 are creating an open textbook on Fundamentals of Injury Biomechanics

- Students in Food, Nutrition and Health at UBC wrote or edited Wikipedia articles on various foods

- Students in numerous courses at UBC have created open case studies on various topics, posted on the Open Case Studies website

Connection

Open Pedagogy

Defining open pedagogy is challenging. Wiley and Hilton (2018)[1] define what they call “OER-enabled pedagogy” in terms of permissions for re-use: “the set of teaching and learning practices that are only possible or practical in the context of the 5R permissions which are characteristic of OER.” For example, asking students to take existing open educational resources (such as a textbook, article, set of slides, or other) and adapt them for their particular course context, would count as open pedagogy under this definition.

Wiley and Hilton (2018) call these sorts of assignments “renewable” rather than “disposable.” Disposable assignments are where students create artifacts that are only seen by their instructor or TA and serve no other value beyond the students’ learning for the purposes of the course. Renewal assignments, on the other hand, are when students post their work publicly with an open license; this is “renewable” because the work is then available for others to later revise for their own context, build on, or improve.

Others offer a broader definition of open pedagogy:

Looking at open pedagogy as a general philosophy of openness (and connection) in all elements of the pedagogical process, while messy, provides some interesting possibilities. Open is a purposeful path towards connection and community. Open pedagogy could be considered as a blend of strategies, technologies, and networked communities that make the process and products of education more transparent, understandable, and available to all the people involved. – Tom Woodward in an excerpt from an interview in Campus Technology

Tom Woodward highlights 3 features of open pedagogy:

- open planning: Prior to the start of a course built on open pedagogy there is a focus on collaboration regarding what the course might be — the content, the lessons, the tools of construction, and the teaching strategies…You can see what other instructors have done — their resources, their lessons, or their reflections on what happened during their course. As Tom points out, these processes are often hidden from public view. Making them open and accessible means that others can learn from them.

- open products: Students are publishing for an audience greater than their instructor. That matters. Their work, being open, has the potential to be used for something larger than the course itself and to be part of a larger global conversation. This changes the experience of doing the work, but just as importantly it changes the kind of work you ask students to do.

- open reflection: After the course, reflecting and documenting how the course went is valuable both to the instructor and to those who might be considering similar courses or pedagogical strategies. People are happy enough to present and document success but it’s still not common practice to reflect on elements that don’t work well. Documenting reflections on what worked and what didn’t and making those public can lead to connections between people working to address the same challenges.

One could also consider a fourth feature:

- open process (of creating OER): If you or your students create open educational resources for a course, it’s useful to share not just the finished resources but also the processes of creating them. Sharing the process can mean many things, e.g., talking about how you made a teaching resource such as a video or podcast (what tools, software, what steps you took, pitfalls you ran into), describing why you created the resource in the way you did (what goals you had, what research underlies the creation of this resource), explaining how you have used the resource in a class and whether it was successful.

Examples

The following are examples of open pedagogy in practice at UBC:

- The examples of open assignments above count as open pedagogy

- Christina Hendricks (Philosophy) does some course planning and reflection on how her Introduction to Philosophy courses go on her blog

Open educational practices

Similar to “open pedagogy,” scholars have defined open educational practices in different ways:

Teaching and learning practices where openness is enacted within all aspects of instructional practice; including the design of learning outcomes, the selection of teaching resources, and the planning of activities and assessment. OEP engage both faculty and students with the use and creation of OER, draw attention to the potential afforded by open licences, facilitate open peer-review, and support participatory student-directed projects (Paskevicius, 2017).[2]

Creation and/or use of open educational resources; adoption of open pedagogies; use of open source and/or free software and tools; and/or open sharing of scholarly practice and knowledge with others (Harrison and DeVries 2019).[3]

These views of open educational practices consider opening up many parts of education, including content, tools, learning objectives, activities, assignments, and peer review.

Open educational practices could include:

- Engaging students in designing learning objectives and activities/assessments to fulfill them

- Inviting and incorporating feedback on the course and its open resources, whether instructor-produced or student-produced, from people inside and outside the course

- One could open an entire course to participants from outside the institution (such as in a MOOC), ensuring that the course elements are openly licensed

Share your process

One way to do so is to have a blog on teaching and learning. UBC provides faculty, staff and students with a free blog site on UBC Blogs. The FAQ on the UBC Blogs page has extensive information to help you get started, and information about drop-in support if you need it.

Teaching with open assignments

In the post What is Open Pedagogy?, David Wiley defines open pedagogy by way of example. He writes about how he blended principles for effective teaching and learning with open practice to create an assignment that has endured the test of time and resulted in some excellent student contributions to open educational resources (OERs).

The components of open teaching practice highlighted by Wiley’s example include:

- Building trust with students – by way of being explicit about the goals and purpose of the open assignment and clear guidelines for what is to be developed.

- Authentic assignments – offer students the opportunity to create something to be immediately used by a real audience (in this case, students were creating a learning resource for peers in their classroom). Since students will be using their resource to teach others, they get immediate and practical feedback. This is in contrast to what Wiley calls “disposable assignments” which are created for the instructor, seen by no-one else, and often discarded at the end of term.

- Offer a clear description of the assignment and examples where possible – many students will be unfamiliar with the process of finding open resources to used in a project and remixing them to create something new – offering a detailed example is helpful.

- Provide scaffolds for learning – Divide the assignment into steps and offer opportunities for feedback after each step so that students are supported in building and improving their work.

- Invite students to license their work – with a Creative Commons license resources can be freely remixed and improved upon by others. Talk about the reason for licensing and offer options for students who choose not to publicly share what they create.

- Offer opportunities for students’ work to be incorporated into the course – either as an example to work from or as a remix to build on and improve.

Renewable, not disposable assignments

Many assignments given in post secondary institutions are what David Wiley calls “disposable”. Renewable assignments, on the other hand, add value to the world beyond earning a mark from an instructor–they provide resources that are useful and usable by others, whether other students in the course or the wider public. Examples could include students creating notes or demonstrations for other students in the same course (and possibly also posted publicly for others), students editing articles on Wikipedia or an institutional wiki site like the UBC Wiki, and students producing research that can be used by a community group. Even those assignments that might otherwise be “disposable” can be made renewable by sharing them with other students in a course and, if the student agrees, publicly.

In order for such work to be truly “renewable,” though, it should be openly licensed to allow others to not only view it but also revise and reuse for their own purposes.

Privacy

A concern that comes up for both students and instructors is privacy. Aspects of both learning and teaching be a private endeavour and teaching in the open requires making decisions about what elements, or course assignments can be completed in the open and what elements may require sharing only between student and teacher or students and their peers.

Student Sharing & Open Assignments

When asking students to create open content and share publicly, there are a few considerations to keep in mind. Students own the copyright in their own work, and should be given the choice whether or not to share or publish it publicly and with an open license.

When sharing content outside of traditional classrooms, different people have different levels of comfort and risk. Students should never be required or compelled to give up any of their privacy in order to complete an assignment. It is always good to provide students with options on how they may complete or share their work.

If you are publishing students’ work on a course site or planning to re-use it in future terms, ask for students’ permission regarding how long they would like their work to be share. Some may not mind having it posted indefinitely, but some may wish to have their work taken down as soon as the class is finished. At the very least, let them know that if they later decide they would like it taken down, they can contact you.

It is useful to provide them with various choices, such as:

- publishing with a pseudonym

- publishing in a way that only other people in that class can see their work

- submitting only to the instructor or T.A.

- publishing publicly with or without an open license

When working with students as creators of content, it can be helpful to think of them as collaborators. You might not want your work or privacy shared without your consent and students are often the same.

Time

As with any change to an instructors practice, developing open assignments can take considerable time on the part of the instructor and in some cases students. To deal with this challenge, instructors can work with instructors who have taught using a similar approach or tool, work with faculty or central support units or with organizations such as Wikimedia that can support these projects

Tools and Technologies

Finding tools that can be used for open teaching can be challenging. There are privacy and FIPPA issues that require navigation. For a better understanding of these issues, see CTLT’s Student Privacy and Consent Guidelines for Instructors.

At UBC we do have open services and frameworks, the UBC Wiki and the WordPress that can support open teaching and learning.

- Christina Hendricks, “Renewable Assignments: Student Work Adding Value to the World”

- David Wiley, “What is Open Pedagogy?”

- David Wiley, “An Obstacle to the Ubiquitous Adoption of OER in US Higher Education“

- Tom Woodward, Open Pedagogy: Connection, Community, and Transparency

- ↑ Wiley, David; Hilton III, John Levi (September 2018). “Defining OER-enabled pedagogy”. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning. 19 (4). doi:10.19173/irrodl.v19i4.3601.

- ↑ Paskevicius, Michael (2017). “Conceptualizing Open Educational Practices through the Lens of Constructive Alignment”. Open Praxis. 9 (2). doi:10.5944/openpraxis.9.2.519.

- ↑ Harrison, Michelle; DeVries, Irwin (Fall 2019). “Open Educational Practices Advocacy: The Instructional Designer Experience”. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology. 45 (3). doi:10.21432/cjlt27881.